We often discuss the identity of a minority group in public discourse as if it’s homogeneous by virtue of being in opposition to the majority.

When discussing contemporary Tibetan identities, we have to take the responsibly to look at each concept individually and question the framework of "identity" as a whole.

W.E.B. Du Bois coined the term “double consciousness” at the turn of the last century in an essay that discusses the experience of African Americans in the US. In the essay, Du Bois identified the feeling of having an identity that’s been splintered into several parts — of “always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tale of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”

The act of being observed and the way in which one is observed can create a disassociation where you are both the subject and an object of fetishisation.

It feels poignant how this “double consciousness” is still experienced by so many POC in the contemporary context. A constant effort to carve out a space that allows you to be a nuanced, dynamic and sometimes contradictory individual, whilst bearing the knowledge that you move through the world with the burden of "representing" your collective minority community.

In the Tibetan context, there are three factors which heighten this schism between one's individuality and one's collective identity.

1, there are simply not a lot of Tibetans as a population.

2, the Tibet narrative in mainstream culture has been shaped chiefly by non-Tibetans. We have been unable to tell our own story both in the People's Republic of China where the CCP's portrayal of the Tibetan identity has been crucial in securing the legitimisation of its governance of the Tibetan people; and in the rest of the world where the Tibetan narrative has been constructed through various Orientialist renderings by Europe and the US.

3, unlike many minority diaspora communities in the West, Tibetans exist as a minority in every geographical context - Tibet in the context of China, the Tibetan exile government and diaspora in India, and Tibetans spread out through the rest of the world (mainly in Europe and the US).

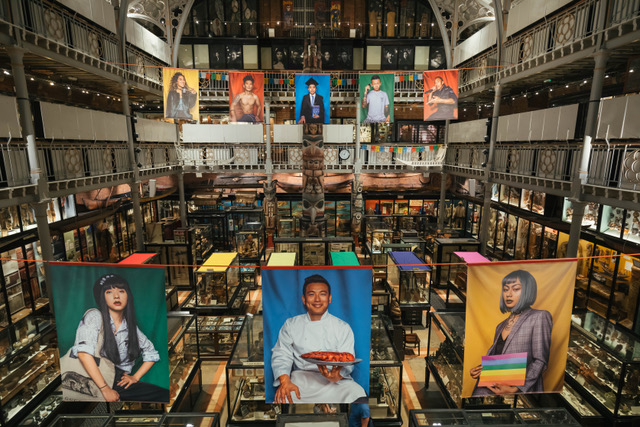

The photographic works and the video created by artist Nyema Droma in the Performing Tibetan Identities exhibition at the Pitt Rivers Museum is ambitious in its aim to create a multi-dimensional picture of young Tibetans living in the contemporary world. The dichotomy of traditional and contemporary identities in the portrait series as a framing device used by the artist can be seen as entrenching stereotypes of Tibetans as being "Either / Or." But if you view the portraits as two ends of a spectrum residing within the subject who moves fluidly along that spectrum, you begin to see the diversity of experiences, points of view, as well as their sense of Tibetaness.

Exhibition creator: Nyema Droma | Courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum

Photographer: Ian Wallman

Exhibition creator: Nyema Droma | Courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum

Photographer: Ian Wallman

Dorje Sornam, living in Zurich has chosen to pose in his Swiss army uniform and rifle. The concept of a Tibetan soldier is definitely counterintuitive to the mainstream idea of Tibetans as a group of peaceful, non-violent, perhaps pitiful Buddhists living a simple ethereal existence.

Tsering Yata from Lhasa poses with a mic and his police uniform, an interesting juxtaposition on its own, but especially in the context of him being a Tibetan working as a policeman whose actions are dictated by the Chinese government.

Sen Chung is a Tibetan nun living in Yushu, a prefecture of the Tibetan Autonomous Region as defined by the PRC. She dons a version of her Buddhist robe in both portraits but she poses with a mischievous wink, hand gestures, and headphones to illustrate her love of rap music. This portrait can inspire a knee-jerk reaction from both Tibetans and non-Tibetans alike, some feel that her identity as a rap fan undermines her integrity as a nun. But I think the power of the portrait lies precisely in this layering of her personhood. She is a nun for whom her religious practices are central to her identity, but she's also a young woman who feels connected to rap music - similar to many young Tibetans - akin to Karma Emchi (Zurich, Doctor/Rapper) also known as Shapaley.

Finally, Nyema Droma's own portrait performs multiple identities as she plays with both gender and cultural identities. She's dressed in a traditional male costume holding a camera in one; and her contemporary portrait sees her as a tattoo bearing, lipstick wearing, and camera-carrying individual who's dressed in an outfit that's very much gender neutral.

Nyema Droma - Lhasa, photographer, designer and entrepreneur

Copyright Nyema Droma

Sen Chung - Yushu, nun

Copyright Nyema Droma

The film which accompanies the exhibition fleshes out these intersectionalities and subtleties even more eloquently. In an essay by the exhibition's curator Clare Harris (Curator for Asian Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum and Professor in the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford), she points out that:

Nyema's photographs function as 'little theatres of the self' (as leading photography theorist Elizabeth Edwards has phrased it), where many facets of identity are performed and allusions to the past, present and future are intertwined. These intimately biographical images, although framed with reference to an earlier essentializing mode of photography demonstrate that no one can be reduced to just a 'type'.

The film also highlights the cultural and linguistic differences between Tibetans who grew up in varying contexts which can be a point of contention amongst the community. When speaking in English you can hear various accents tinted by Germanic, American, British, and Indian tones. When speaking in Tibetan, the various interviewees intermix their Tibetan with English, Mandarin, or Hindi. One of the participants pointed out that they used to be angry at Tibetans living inside Tibet for using the language of the Han Chinse, but later realised that it was the same as him using Hindi to fill in the vocabulary gaps of his Tibetan.

The development of the Tibetan lexicon has been fractured and halted due to its political history. Inside of Tibet, the working language is Mandarin as with the rest of China. Therefore both practically, and endorsed by specific policies, the development and usage of the Tibetan language has been sidelined. The communication wall between Tibetans living inside Tibet and those on the outside has also led to many misunderstandings and misconceptions of how the other lives.

Nyema's images hence also bring to the forefront the question of self-representation through images and the agency it gives the story-teller, especially when we, as second-generation Tibetans are living in an age of social media. It also opens up a channel for young Tibetans separated by borders to glimpse into each other's identities.

Tenzin Seldon

Tsunaina

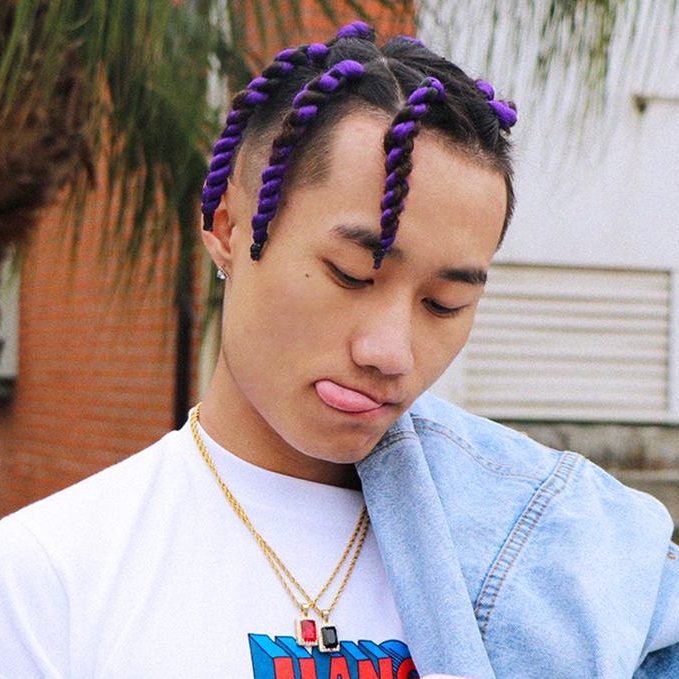

Young13dbaby

Tenzin Mariko

The absence of Tibetan representation in the mainstream discourse in all of the previously listed geographical contexts where Tibetans reside has been filled by a robust roaster of personalities on social platforms. From entrepreneurs like Tenzin Seldon (US), to the fashion model Tsunaina (Europe, UK), Pema Tenzin (Tibet), AKA Young13dbaby, a rapper who recently performed at SXSW, and Tezin Mariko (India), a former Buddhist monk who is an openly transgendered model ... social media has opened up spaces where these Tibetans are individuals first, and Tibetan second.

The representation of Tibetans we see online also shapes the way that we see ourselves offline. The informed identities we view ourselves through is no longer shaped only by the prevailing narratives constructed by the "majority," but by complex stories told by people who are just like us.

With time, perhaps the "double consciousness" can slowly become dissolved to be less fractured and splintered.